To explain, I originally wrote a piece criticising the website Anime Feminist (Anifem) and its creator Amelia Cook back in 2016 some months after it launched. My main issue with the writing and the website itself was that it failed to understand Japanese pop culture as a whole and bizarrely viewed it through a weird myopic western feminist lens. I felt it was a really bad approach and applying western feminist dogma was very unhelpful in understanding something which had its own unique evolution, visual grammar, stylistic devices and even genres. Even worse was the deliberate misinterpretation of the material and to a large degree demonisation of specific sub-fandoms. I was also extremely cynical of Cook’s motivations for creating the website. I suspected that she saw Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency website and wanted to make something similar in order to beef up her resume or to gain a higher profile.

|

| Apparent Anifem critic as perceived by the site's staff |

A lot of water has passed under the bridge since the website was launched. The site’s creator, Amelia Cook, deregistered the site as a business in the UK sometime in 2018 and left the website in 2019 after experiencing burnout. Just over a year ago, both her twitter accounts went silent. Caitlin Moore, Dee and Vrai Kaiser became the website’s managing editors in 2019. Another thing I’ve noticed was the initial support in the first two years of the website’s inception, mostly from many well-known people in the anime community, bafflingly seemed to practically evaporate soon after. Regardless of how well written or thought provoking an article might be, very little of the material published seems to make it out beyond their small core of supporters.

|

| Anifem's dog whistling paying dividends |

To begin with, I have to admit there has been some excellent articles published since I last wrote about the site, notably to do with anime and manga for women in general, as well as genres within those two types of media that women would enjoy (with most of these written by outside contributors). However, much of the material published is mostly in the form of negative criticism of Japanese pop culture. And while that I agree that Japanese pop culture should not be free of scrutiny and criticism, when the vast majority of material published is negative or at least contains some negative elements within it, I sort of find myself questioning if the core staff of Anifem actually enjoy anime or other Japanese pop culture at all.

|

| Winning hearts and minds yet again |

I recall one reader complaining about the number of articles dedicated to “Darling in the Franxx” versus material their readers would actually like. Vrai Kaiser responded by saying they didn’t set out to do that and it was untrue. But the reader fired back by noting there were more search hits for “Darling in the Franxx” than there were for Yaoi. And this is a more than a fair argument. You have to question why so little time and energy is dedicated to exposing their readers to material they may like. Apart from one single article on shoujo manga from the 1970’s and a couple of articles on Yuri and Yaoi, few classics of the genre, mangaka or female anime directors are rarely mentioned, let alone given full length articles.

|

| Murasaki Yamada |

Even when the material they are critiquing offers up excellent avenues to explore the talented women in the industry and the history of women in fandom, they seem to be either totally ignorant of it or deliberately avoiding highlighting them. For example, a podcast episode of theirs explores the movie “Miss Hokusai (Sarusuberi)”, but bafflingly only mentions the author of the original manga, female mangaka Hinako Sugiura, in passing. They either seem ignorant or utterly uninterested in Sugiura’s history, including the fact she was initially an assistant to prominent feminist mangaka Murasaki Yamada. Considering that the website is called “Anime Feminist”, I found this omission rather curious. Reviews of currently airing anime include most shows streaming on Crunchyroll and other streaming services, including shows their readers would clearly not be interested in. Meanwhile shows which did not fit their myopic review criteria, like “Little Witch Academia”, were ignored because Netflix wasn’t streaming it weekly like most simulcasts. This is despite the fact it clearly was in line with what their viewers enjoyed. “Little Witch Academia” was eventually the subject of their podcast, but that is literally the only time the series has been mentioned.

|

| Kyoto Animation main studio |

I also question their comprehension of complex issues and wonder if they only understand them beyond having a superficial knowledge of them. For example, when they decided not to review “The Rising of the Shield Hero” as they felt the show had themes of rape and slavery apologism, they instead they posted a list of Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) that dealt with stamping out modern-day slavery and gave assistance to survivors of rape and abuse. That’s all fine and dandy, but they managed to fuck it up big time by initially including the Polaris Project, an anti-sex worker, religious right NGO that most certainly highly inflates their statistics in terms of human trafficking. Readers were rightly outraged by this, and although Anifem apologised and took down the link to the NGO, they still kept the link to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, which is run entirely by the Polaris Project. How they didn’t know that is beyond my comprehension. Polaris’ logo is displayed prominently at the bottom of the website.

|

| After the Rain |

Now I'm all for discourse on titles which may have the potential to be controversial, like “After the Rain”. But the article takes key scenes out of context and deliberately misrepresented what happens. A laundry list of scenes the author had issue with, which includes links to screenshots, are far, far tamer or totally mismatched to their rather salacious descriptions. Many were taken completely out of context. It is quite apparent that the show is heavily influenced by shoujo manga, even though the original work was published in a seinen magazine. Aping this style doesn't necessarily set out to sexualise Akira, but this is all the author sees; a woman in a seinen manga is only there for sexual gratification of the male audience. The author can't empathise with the audience or see them as anything but predators or potential sexual abusers. It's quite odd but also rather telling.

|

| Bubblegum Crisis |

Some articles have premises so absurd you’d think they were satire. Take for example “Love & Lies: Case Closed and the normalization of gaslighting in fiction”, in which the author, with a straight face, suggests that “Detective Conan’s” titular character, Conan Edogawa, is gaslighting Ran Mori because he has to keep tricking her into thinking her boyfriend, Shinichi Kudo, is still away overseas when in fact Conan is Kudo and has been shrunk to the size of a small boy by an experimental drug. See, I told you the premise of the article was absurd. Now it’s hard not to admit some of the writing and situations in “Detective Conan” are silly beyond belief, but one can only assume the author is completely unfamiliar with how fiction is constructed and presented to an audience, especially in long running franchises like this one where the “reset button” technique is used at the end of each episode in order maintain the status quo of the setting and characters.

|

| Detective Conan |

Another issue I have with the writing is constant outdated stereotypes, myths and straight up othering of sub-fandoms. In the past Cook and the website have not been not been too complementary to fandoms centring around moe and idol fans and have suggested that sexist media creates “harassers”, which has no scientific basis in reality. In a response to what can only be described as an actual harasser on twitter, Anifem’s account stated “We never made any statements about the people watching the show. The stories someone enjoys are not indicative of their personal moral character and we've never stated otherwise. We analyze and critique fiction, not the fans of that fiction”. This statement is patently and demonstrably false.

|

| Why was this particular screenshot of a Momoiro Clover Z concert used to illustrate the idol culture article I wonder? |

Reading the article, you get the impression that women do not exist in idol fandom, that the insanely popular boy bands on Johnny & Associates’ roster don’t exist, acts like Ladybeard, anti-idol groups BiS/BiSH apparently don’t exist, and the explosion of alternative idols in the last decade apparently was a figment of people’s imaginations. You would also believe that female “Love Live!” fans were non-existent too. Yet again, we see the exclusion of inconvenient truths and realities in order to force fit the narrative the author is trying to push. Even if they don’t explicitly criticise fans of certain anime or genres, they do enough dog whistling to appeal to the prejudices of their readers. And the dogs bark back. Sure, a second excellent, far more balanced article on female participation idol fandom was published several months down the track, however it was too little, too late in my opinion.

|

| Otaku no Video |

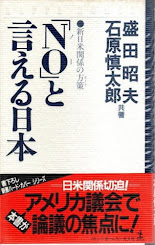

I could go on and on, bringing up dozens more examples where you could only conclude authors deliberately misinterpreted storylines to fit narratives they were trying to push, ignored positive elements in manga and anime to dwell in mindless negativity, and perpetuating false and negative stereotypes of fandoms they took issue with. Instead, I want to bring up the elephant in the room; where does the website and the main staff sit in terms of their feminism? I think a lot of their views do sit comfortably in a moderate, mainstream type of feminism. However, it’s patiently clear that when dealing with themes of expressions of sexuality, it is really hard not to label a lot of the published views as sex-negative with some views heading into radical feminist territory.

In a winter 2018 summary of anime series for that season, Vrai Kaiser bizarrely described the pinkish knees on the female characters in “Citrus” as “blowjob knees”. In another recent seasonal review, Vrai again implied another set of female characters which also had the same feature and again that apparently meant they were also fellatio aficionados. I’m really not sure if Vrai has some issue with fellatio, but I do find it rather telling that she will on occasion bring this up in relation to female characters. Recently a reader rightly criticised Vrai’s specific, odd, prejudicial language in terms of female anime characters that have pinkish knees. With this complaint being from one of the “core demographic” and therefore they could not dismiss it as an “attack” as they normally do, they apologised, removed the offending language from the review and said it was a joke. It was patiently obvious it was not.

Anifem’s moralism around sexual expression and fantasy does not stop with female characters. It applies to fandom and more broadly, women. Caitlin Moore’s article on the manga “Horimiya”, BDSM and potential abuse in relationships starts out with her berating her own mother for defending “50 Shades of Grey”. Moore then trots out the old, thoroughly debunked Media Effects model, by suggesting that young people develop their ideas about relationships from fictional media, not from their close family and the communities they live in (yes, even in ones where sex education is non-existent). Putting that aside, it does feel odd to dump sex and relationship education on to fiction and criticise it for doing “a bad job” of it, when in reality the issue is clearly poor and/or inadequate or even non-existent sex education polices of governments and schools.

At any rate, it all reeks of a Mary Whitehouse mindset where fiction must change or fit their narrow, myopic morals and ethics in order to pass muster in their eyes. And it does feel similar to the techniques and language Christian fundamentalists like Whitehouse used (and continue to use), especially when shonen manga and anime titles are being criticised. Wrapping it up in progressive language does not make it less authoritarian than when Whitehouse or her contemporaries did it.

When I was involved in campaigns to stop the Australian internet being filtered more than 15 years ago, I would often come across far right Christian groups masquerading as feminist groups. One of their side issues was that of female pop singers sexualising themselves. These groups would often complain about the overt sexuality of Lady Gaga, Rihanna et al. The main argument was that the complainers could not find any female singer who wasn't “sexualised”. But then I would counter with a list of female singers who weren't; Polly Harvey, Florence Welch, Missy Higgins, Sarah Blasko, Kim Deal etc. And then they'd go silent. As you can see, the issue wasn’t that they wanted artists who weren’t “sexualised”, they wanted Lady Gaga and Rihanna not to be sexual. And there was their agenda laid bare; they did not really care about finding media or singers that were to their liking. They wanted to change stuff they didn't like. And I highly suspect this is mindset of Anifem as well.

|

| Naoko Yamada |

And if they are interested in women and anime as they claim, why are there no articles on women in fandom? Why is there nothing about the large female fandoms for franchises such as the original “Gundam” TV series and “Saint Seiya” for example? Why is there nothing about how female artists totally dominate Comic Market (Comiket) every year and have done so since its inception in 1975? Of course, anytime anyone asks any of the key staff why there isn't any articles like these, the answer is always the same; send in a pitch. Meaning, we the readers have to do the work for them. Seeing as they are always crying a poor mouth and asking for donations to fund their website and writers, why can’t they instead put some of that money towards searching out and commissioning people to do research and write articles about women and anime?

|

| Large group of female fans trading badges in the rain at Naka-Ikebukuro Park, photographed by myself, circa Autumn 2013 |

But of course, they aren’t doing any of this stuff. In fact, no one really is, and it can be extremely difficult to find articles or information about any of these things, especially in English. But that’s my point; why on earth would you create a website dedicated to women and anime (even if it has an ideological bent) and not really explore the topic? How is reviewing seasonal anime like the latest titty-filled fanservice show that your readers would not watch in a million years helpful to anyone at all? Unless your point is to feel morally superior because you’re so sophisticated that’d you’d never watch that “trash”? They also seem to have the condescending attitude that anime fans are uncritical of what they watch and consume. If don't agree that whatever this new season's “controversial” show is awful (usually some trashy exploitation or genre anime), then you're the problem, not them.

|

| Top notch writing |

I honestly could not imagine viewing all the media you consumed through the myopic lens of a rigid ideology. Imagine how tiring and tedious that would be. You can enjoy "problematic" material and still be a well-rounded, socially progressive person. It's not that hard. Humans are more than their personal beliefs, ethics and morals, and to a large degree people’s media choices do not have to comply 100% to their own personal beliefs, ethics and morals. For example, someone may enjoy the crime thrillers of Quentin Tarantino does not mean they subscribe to the ideals of his film’s protagonists. It would utterly absurd to suggest that fans of the TV show “Dexter” would empathise with and support serial killers. However, this is thought process seems to permeate through many of their articles and reviews throughout the website.

|

| Just adding to the ridiculous existing moral panic about anime and manga... |

Five years of Anifem has brought us very little valid criticism. Mostly it's been a lot of hand wringing, tut-tutting, bolting on tired ideologies to the usual franchises where there are none, wretched, outdated views of what male fandom supposedly is and lots of gnashing of teeth. I really don’t understand the purpose of the site at times or understand why or how the writers became fans of anime and other Japanese pop culture. If you have so many issues with it and can’t reconcile your own personal ideology with it, why on earth are you a fan?